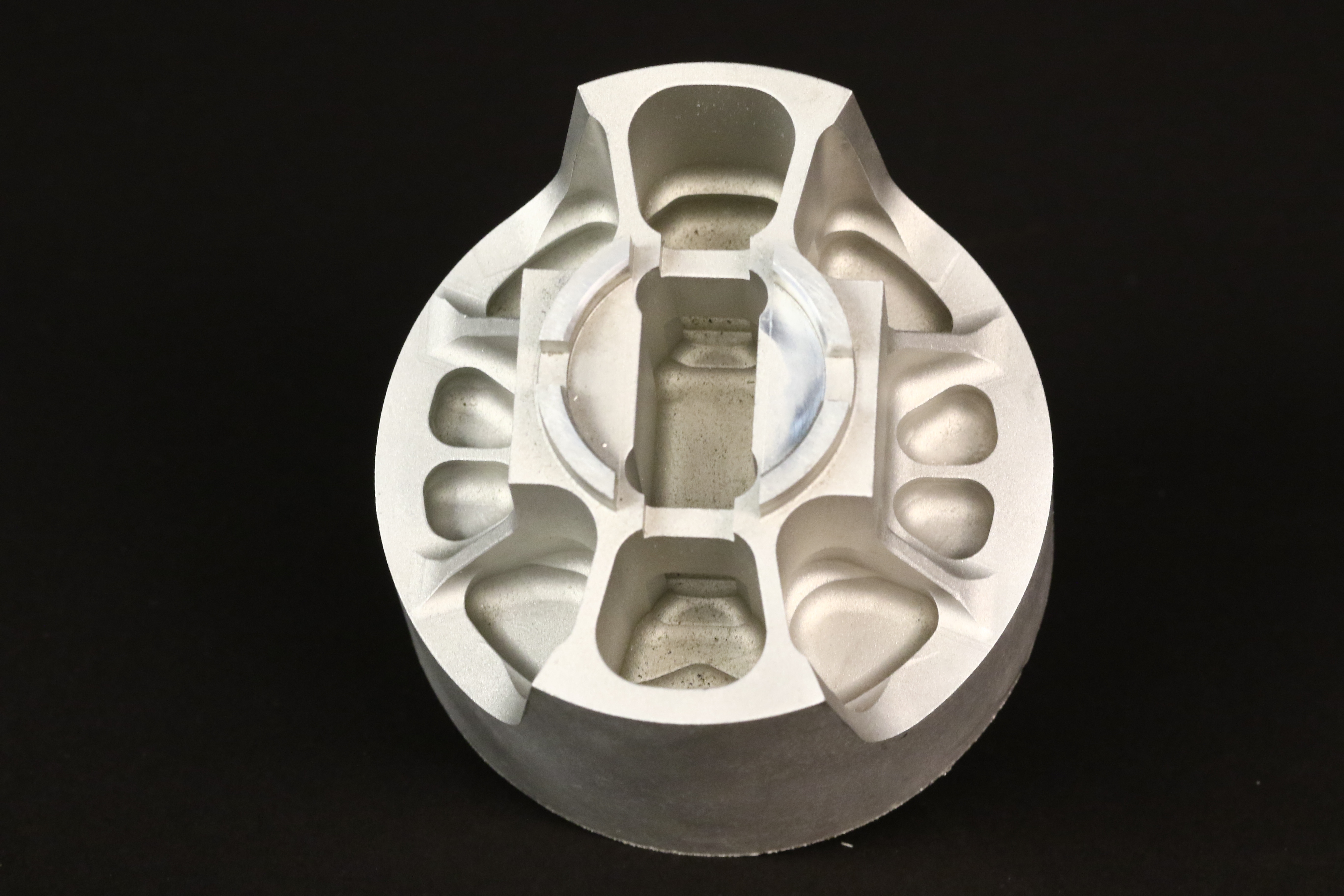

Bead blasting the bottom surface of billet pistons helps to eliminate stress risers and makes for a more robust foundation.

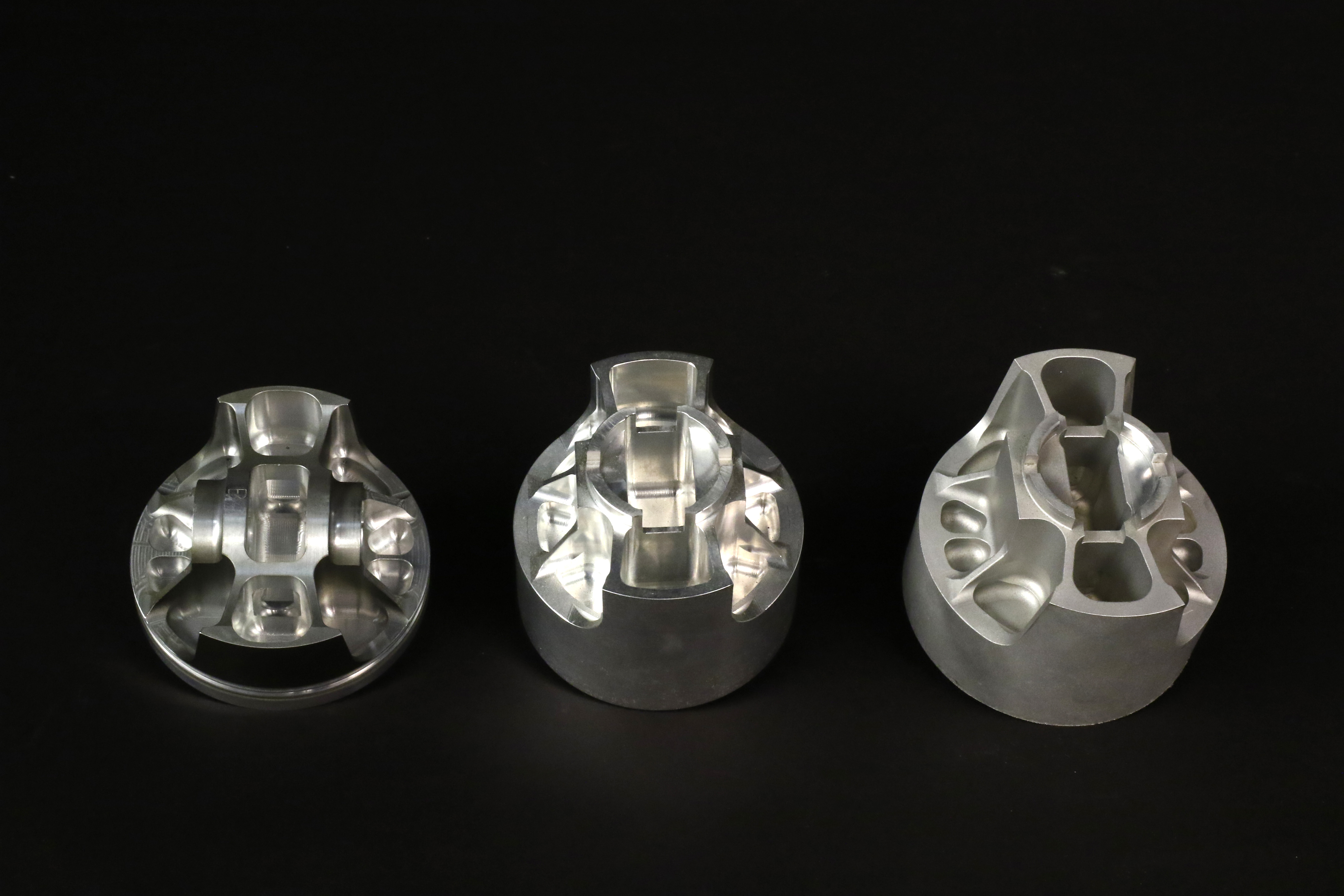

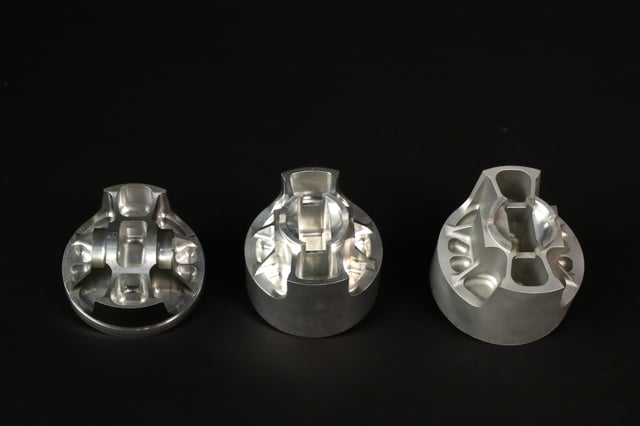

Is a shiny surface the best approach for a billet piston finish? There are different schools of thought driving the answers to this question. Of course, any response will be relative to the different design elements associated with a piston. For example, shiny is not useful on the skirts where a low-friction coating is applied. So, let’s confine this discussion to the piston crown, both the top and bottom.The question is often raised because piston manufacturers may media-blast the underside of a billet piston, leaving a frosted finish in place of tool marks from the various passes of a CNC machine. Since billet pistons are almost always custom ordered, some engine builders worry that the blasted finish is obscuring a potential problem with the metal.

“Some people think that bead blasting hides something, such as a mistake in machining,” says Clayton Strothers, an engineer at JE Pistons. “Some customers like the way billet looks and want to see how the part is machined.”

Aesthetics aside, there is a logical reason for blasting the underside surfaces of a billet piston.

Want to learn more about pistons? Click Here.

“Machining may leave a roughness or small peaks and valleys that could result in a stress riser,” explains Strothers. “Bead blasting will help smooth all that out and reduce the potential for stress.”

The strategy is similar to detail work many engine builders perform on the top of the piston crown. Following machining of the valve pockets or dome area, sharp or hard-corner edges may remain. Meticulous engine builders will use sandpaper or a small rotary tool fitted with abrasives to smooth over those areas.

“For the same reasons you don't want sharp edges on the top of the piston, you don't want them on the underside of the piston either,” says Strothers.

A stress riser is basically any force in the metal that is concentrated. If this concentrated stress is greater than the overall material strength in that area, then there’s the potential for a fatigue crack to originate. Considering the high-heat and intense-pressure environment in which a piston must operate, even the smallest hairline crack could lead to a catastrophic failure.

The blasting procedure falls among the middle steps in the manufacturing process of a billet piston. The billet core, or puck, is first heat treated, then machined to the basic shape and dimensions that are somewhat similar to a raw forging.

The media used by JE is a mix of stainless shot and grit. It’s applied in an automated process that also washes the billet of any leftover residue. In some special applications, a glass bead will be applied by hand.

The blasting will remove sharp edges, superficial scratches and minute tool marks. The resulting clean appearance materializes from the thousands of tiny, soft dimples left in the surface from the blasting media. These round-bottom indentions scatter the light to produce a satin-like appearance in addition to eliminating stress risers.

“It makes for a more uniform surface,” adds Strothers. “This happens after the underside is machined out before any critical operations, such as machining the skirts or ring grooves. There is no chance of ruining the critical elements.”

Once the blasting and cleaning is complete, the piston has a register placed so the skirts, valve reliefs, dome and ring grooves can be CNC machined. Even though there is no downside to media blasting the underside of the piston, many engine builders still prefer a shiny surface. Billet pistons are often ordered for development and R&D purposes because design changes can be made quickly (http://blog.jepistons.com/billet-versus-forged-pistons-whats-the-difference). Engine builders, therefore, may want to make detailed inspections of the metal surfaces after engine teardown.

“Some customers just like the way billet looks. They want to see how the part is machined,” says Strothers.

There used to be a school of thought in some engine shops that a blasted surface on the topside of the piston could be beneficial. Carbon buildup in the combustion chamber can be a problem, especially if hot spots develop and lead to preignition or affect heat transfer. Some engine builders accepted the premise that carbon was going to build on the piston crown and a blasted surface might lead to a more even coating that actually acts as an insulator for the piston.

That theory has pretty much been debunked and now many engine builders are opting for polishing the piston-crown surface in addition to smoothing out rough edges and hard corners.

“Now the carbon can’t adhere to the piston surface,” says Strothers.

Blasting is not just for billet pistons. When the initial forgings come out of heat treating there may be residual scales. “It actually looks black on the underside of the piston,” says Strothers. “We’ll use blasting to remove that buildup.”

Since most billet pistons are bespoke to meet specific engine designs or reduce turnaround time associated with special forging tools, the customer has the choice of blasting or not—in addition to many other custom options. Some off-the-shelf billet pistons may have the blasted undersides; again, as precautionary measure to eliminate stress risers.

“Bead blasting is not critical to performance,” sums up Strothers. “It's just another of the little things we do to benefit the piston for the customer.”